Peggy Curran of The Montreal Gazette talked to me, Charles Acland and Will Straw about the legacy of Marshall McLuhan. Here’s an excerpt from the article:

Wershler contends that those who focus on McLuhan as a technological fortune-teller are missing the point. McLuhan, he says, was really a poet who was at his best conjuring up those “philosophical bumper stickers” for which he is best remembered.

“McLuhan was not a futurist. In fact, the later you get in his work, the crappier it is.” He argues that McLuhan, who had studied at Cambridge University before returning to work at U of T, was probably more familiar than anyone else in Canada at the time with what was happening among modernist writers and artists in Europe in the early part of the 20th century. It was with thoughts of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, the poetry of Ezra Pound and the Cubist paintings of Pablo Picasso, says Wershler, that McLuhan concocted his phrase ‘probes’ and envisioned the newspaper as a mosaic, where a reader could absorb the world’s events in any particular order or disorder.

Here’s the full article.

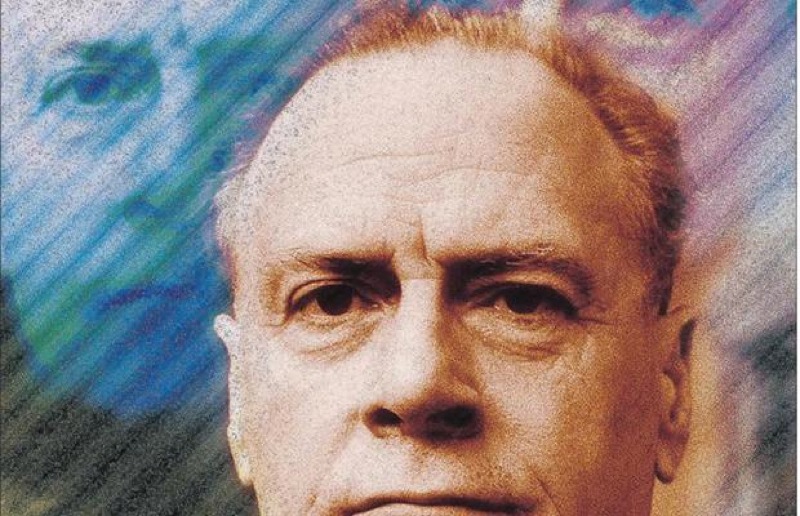

Featured Image by John Reeves and Robert Cross, from the story.