The redoubtable Trevor Haldenby mentioned the existence of this document to me at TEDx Waterloo the other day, and it was too good not to track down.

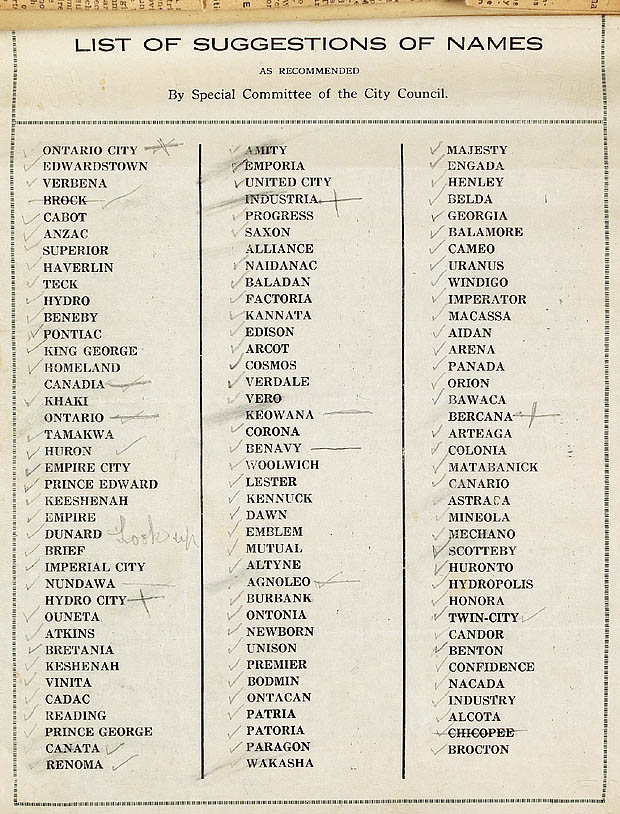

Created by city council in 1916, it’s a list of “Parallel Kitcheners”: suggested names for Berlin, Ontario, during the period before it changed its name to Kitchener. Originally settled by a largely German immigrant population, Kitchener was known as the Town of Berlin from 1854-1912 and the City of Berlin from 1912-1916. As WWI approached and anti-German sentiment rose, other Canadians began to express growing doubts about whether or not the people of the very Germanic-sounding Berlin, Ontario were doing everything they could to support the Canadian war effort … hence the name change.

Looking at the list now, I wish I lived in Mechano, Hydropolis or Industria. I may well have to begin the process of transforming Kitchener into one of them at a speed that keeps my activities slightly below the conscious level of its citizens.

(from the John A. Lang fonds of Library and Archives Canada).